ESA's Euclid celebrates first science with sparkling cosmic views

The European Space Agency recently released the first spectacular images captured by the Euclid space telescope, which are four times sharper than those from ground-based telescopes. They also introduced the first suite of Euclid publications describing the mission’s scientific programme, instruments, and simulation methods. Researchers from Hungary's HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences (HUN-REN CSFK) joined the Euclid Consortium this year.

In collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), the Euclid Consortium has been planning, building, and is currently operating the Euclid space telescope mission. This mission aims at mapping the extragalactic sky over a period of six years, providing unique data that can offer new insights into dark energy and dark matter. Launched on 1 July 2023, the telescope successfully began its cosmological survey on 14 February 2024.

International opportunities for young Hungarian researchers

Within the consortium, HUN-REN CSFK researchers not only analyse simulated galaxy catalogues and test early data but also play a leading role in the Collaboration's science communication programme, drawing on the expertise of the Svábhegy Observatory's communication team.

With support from the Momentum Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), Momentum researchers are collaborating with István Csabai, a professor at the Department of Physics of Complex Systems at Eötvös Loránd University, Gábor Rácz from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and István Szapudi from the University of Hawai'i. This initiative provides opportunities for many young Hungarian cosmologists and astronomers to gain international experience.

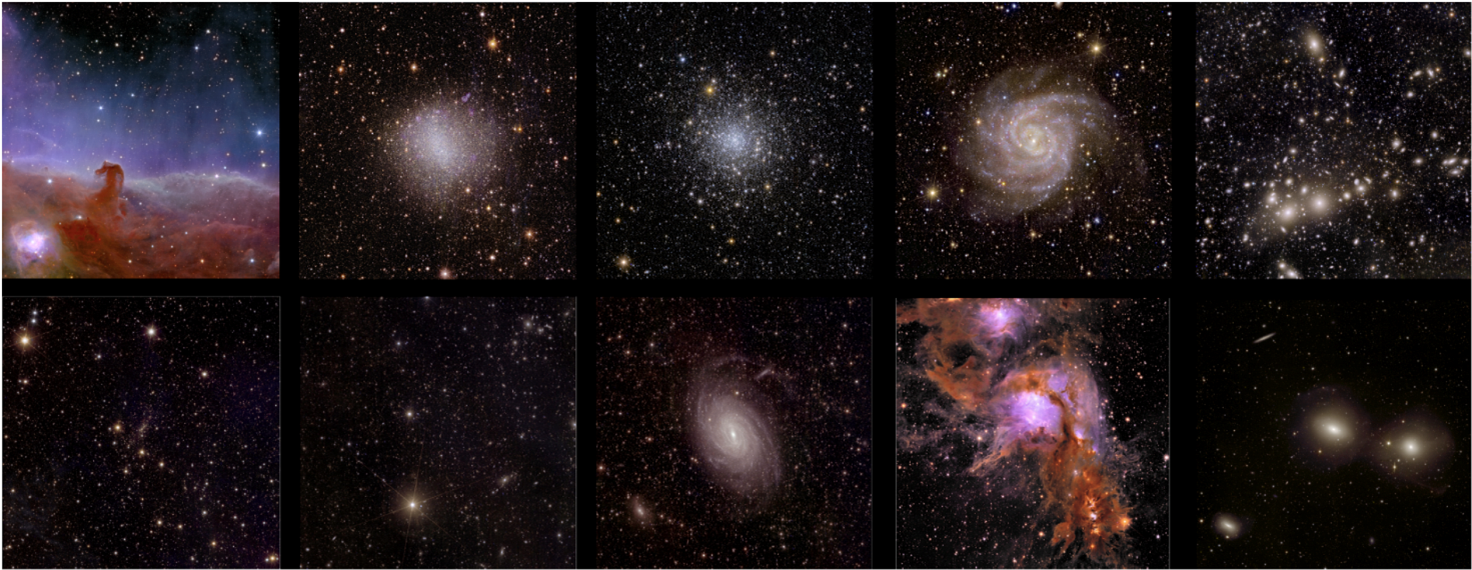

The first ten Euclid ERO images. Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi

Mapping the visible Universe

“The ultimate scientific goal of the Euclid collaboration is to understand the two most mysterious components of the universe, dark matter and dark energy,” says András Kovács, senior researcher at HUN-REN CSFK. “They are called dark precisely because they are very difficult to study directly. We can infer their presence and effects from the distribution of visible matter as well as the shape and clustering of galaxies.”

The basic idea of the Euclid project is that the bigger the map of the visible Universe and the further we look into it, the better we can map the evolutionary history of the cosmos. As the Universe has been expanding since the Big Bang, the further out in space we look, the further back in time we can see (as distant celestial bodies are seen in their previous state, even billions of years ago).

The Euclid space telescope, launched on 1 July last year, is currently undergoing test operations, and the incredible quality of the images of known objects is proving to its supporters and the public that it is not just a working instrument but an examination tool that could open a new era in our understanding of the most fundamental properties of the Universe.

There are two different detectors on board the Euclid space telescope: the VIS instrument makes observations in the visible light range and takes exceptionally sharp photographs of the Universe. This gives us a very detailed view of galaxies and stars, but only an approximate estimate of the third dimension, the distance to celestial bodies. In contrast, the NISP instrument is an infrared detector that can also perform spectroscopy. This means that it can also look at the redshift of galaxies, which gives a much more accurate estimate of their distance and enables the creation of a real three-dimensional map of the Universe.

Unprecedented results

The full set of Early Release Observations (ERO) programme targeted 17 astronomical objects, from nearby clouds of gas and dust to distant clusters of galaxies, ahead of Euclid’s main survey.

Euclid produced this early catalogue in just a single day, revealing over 11 million objects in visible light and 5 million more in infrared light. This catalogue has resulted in significant new science. The images obtained by Euclid are at least four times sharper than those we can take from ground-based telescopes. They cover large patches of sky at unrivalled depth, looking far into the distant Universe using both visible and infrared light.

Future milestones

The next data release from the Euclid Consortium will concern Euclid’s nominal survey. A first worldwide quick release is currently planned for March 2025, while a wider data release is scheduled for June 2026. At least three other quick releases and two other data releases are expected before 2031, which corresponds to a few months after the end of Euclid’s initial survey.

This breathtaking image features Messier 78 (the central and brightest region), a vibrant nursery of star formation enveloped in a shroud of interstellar dust. This image is unprecedented – it is the first shot of this young star-forming region at this width and depth. Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.

Here, Euclid captures galaxies evolving and merging ‘in action’ in the Dorado galaxy group, with beautiful tidal tails and shells seen as a result of ongoing interactions. Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.